Category: Longform

You are viewing all posts from this category, beginning with the most recent.

Fairness, Reach, and the Legacy of Heavyweight Boxing

In Brief

The history of heavyweight boxing reveals how physical attributes like weight, height and reach (arm span) shape competition—and why skill and strategy are the only tools smaller fighters have to try to even the odds. From George Foreman to Jimmy Young, this piece explores what boxing teaches us about fairness in sport, and how natural advantages complicate the idea of a level playing field.

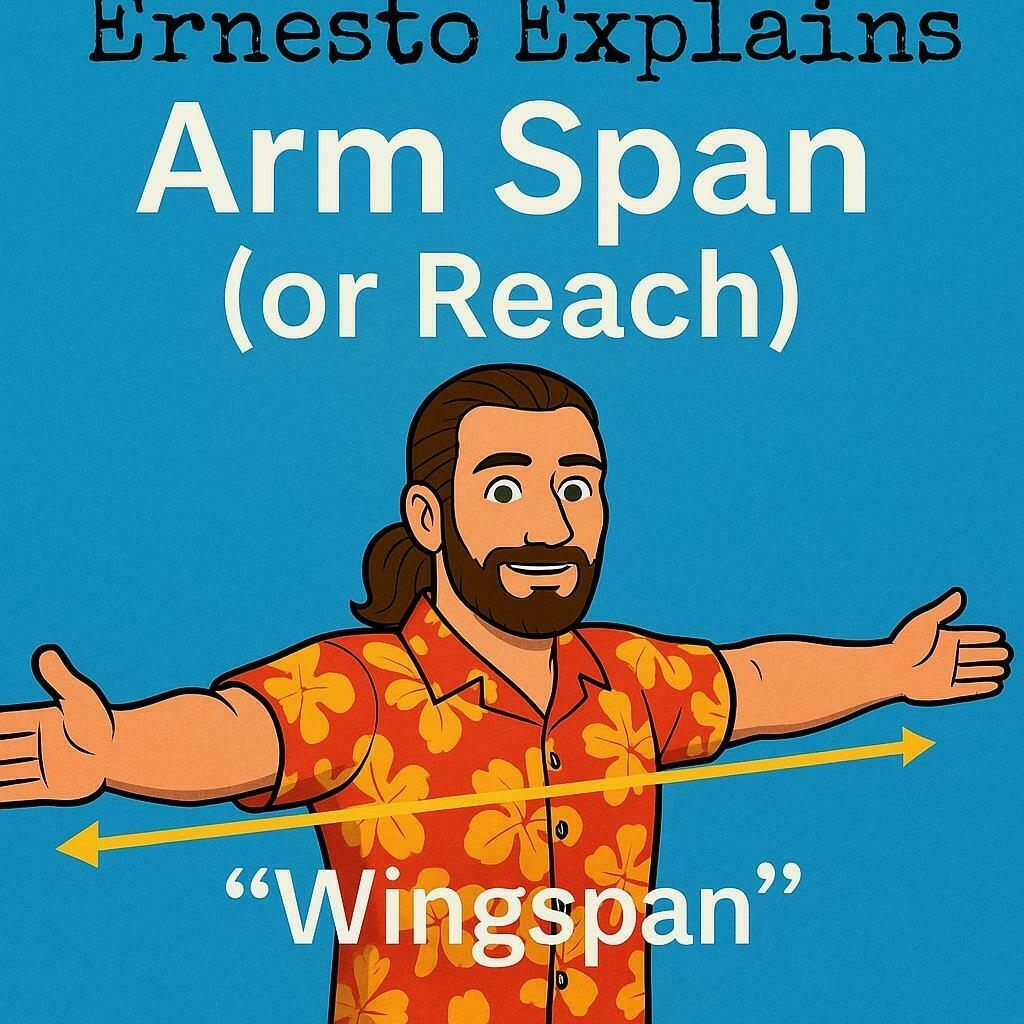

With the recent passing of George Foreman, I started browsing the pages of Foreman and his main opponents of the era and looked at their height and reach. Of course, the whole reason that weight, size and reach are mentioned on the wikipedia page of boxers is that these physical determinants clearly have a strong impact of the performance of a boxer. Weight is the most obvious one. So obvious that boxing associations have long ago divided the competition into the weight categories. This is necessary to give lighter athletes a chance at competing at all. But height and reach are also important and different from weight, since an athlete can change weight within certain limits, while height and reach are mostly fixed once you reach full physical development.

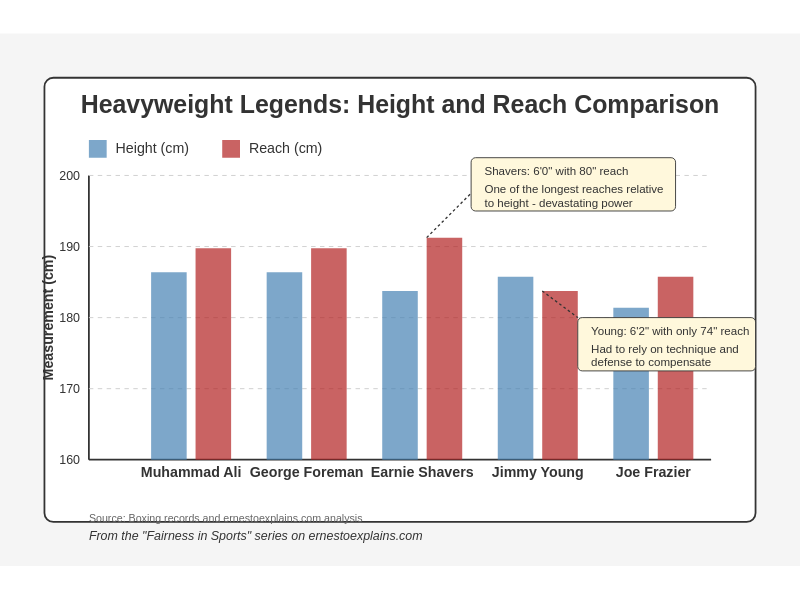

Now, Foreman stood at 6'3" (191 cm) with a reach of 78 inches (198 cm), identical to Muhammad Ali. That symmetry made their historic 1974 championship fight as much a battle of minds and styles as of bodies. It also means both follow a common pattern in high level boxers: a reach that exceeds their height. The explanation is rather obvious: longer arms allow you to punch your rival while he is too far away to be able to punch you back.

Other fighters of that time weren’t so evenly matched. Consider Earnie Shavers—6'0" (183 cm) but with an surprising 79-inch (201 cm) reach and a reputation for the most devastating punch in boxing history. It’s hard to ignore the connection between his long reach and his devastating punch. His long arms probably amplified the force he could deliver, thanks to the physics of torque and angular momentum.

Then contrast that with Jimmy Young, who’s style was sometimes considered “awkward” or “defensive.” At 6'2" (188 cm) with a “below average” 74-inch (188 cm) reach, Young had one of the shortest reaches among top-tier heavyweights. Yet he went toe-to-toe with both Ali and Foreman. How? Technique. Defense. Ring IQ. He turned survival into strategy.

Young’s career points to something deeper: when physical attributes like reach, height, or explosiveness offer a built-in edge, the only real counter is skill—and skill must be learned. In this way, sports are not fair. They are shaped by genetics first, and only then by effort.

This isn’t just boxing. In basketball, does Fred VanVleet have the same room for error as Giannis Antetokounmpo? Of course not. But Fred survives—and thrives—by mastering every inch of his shorter frame. Skill narrows the gap, but the playing field is uneven from the start.

And that’s the reality of competition, in boxing and beyond.

Series Note – Fairness in Sports

This article kicks off our new series on Fairness in Sports.

Over the coming weeks, we’ll explore how genetics, body types, socio-economic factors, and training environments shape athletic competition—often in ways we overlook. From basketball to swimming, sprinting to cycling, we’ll ask: when the starting lines aren’t equal, what does fairness really mean?